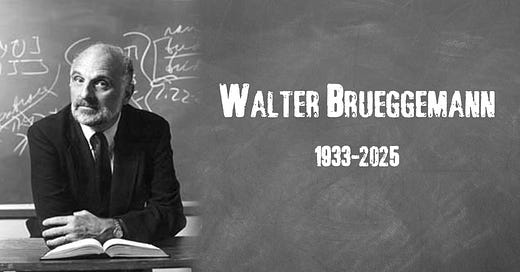

The Legacy of Walter Brueggemann

We lost a giant yesterday. Walter Brueggemann passed away at 91. For those who don’t know, Brueggemann was one of the most influential Old Testament scholars of the last century — maybe ever.

Am I My Brother’s Keeper?

We lost a giant yesterday.

Walter Brueggemann passed away at 91.

For those who don’t know, Brueggemann was one of the most influential Old Testament scholars of the last century — maybe ever.

He helped an entire generation of pastors, scholars, and everyday readers see the Bible as something deeper, stranger, and more alive than the flat version many of us were handed.

Walter and I weren’t close.

But we were in a few meetings together about a decade ago. And more significantly, we had one lunch.

I’ll never forget that lunch.

At the time, I had left full-time ministry and launched my production company. But I still felt drawn to telling some of the Bible stories I had always loved — just in a new way.

So my creative partners and I created a series of one-man shows: Genesis, Exodus, Luke, John, and Acts — five shows over 18 months.

While I was writing Genesis, I reached out to Walter and asked if we could have lunch.

To my surprise, he said yes.

I had an agenda. I wanted his insight. And, if I’m honest, I wanted to impress him.

We sat down. He was kind, warm, but also… Walter.

Without much small talk, he looked at me and simply asked:

What question do you think Genesis is answering?

I took a few stabs.

Where did we come from? I offered.

He shrugged. Not really.

Who is God?

No.

I started running through the book in my head — Creation. Fall. Flood. Babel. Abraham. Isaac. Jacob. Joseph. So much Joseph. Kind of disproportionate, honestly.

Then I thought maybe I had it.

How did God’s people get to Egypt?

No.

It’s in there, he said. It’s the first question a human ever asks God in the text. And the whole book answers it.

I stared down at my pasta.

The first question? Adam? Eve? Noah? My brain was racing.

Chapter four, he said.

Cain and Abel.

Am I my brother’s keeper? I finally said.

He smiled gently, sipping his soup.

Then he simply said:

So tell me about the brothers.

Isaac and Ishmael, I said.

Were they good brothers? Did they keep one another?

No, I said.

Go on, he said.

Jacob and Esau.

He didn’t even have to ask.

Not good brothers, I said.

No, they weren’t. Go on.

The sons of Jacob. Not good, I said. They sold Joseph into slavery.

He looked at me, one exceedingly bushy eyebrow lifting.

You sure? he asked.

I ran the story in my head.

Joseph — the younger brother sold into slavery by his brothers — who rises to leadership in Egypt. Years later, his brothers return during famine, not knowing who he is. Joseph recognizes them. And he welcomes them, feeds them, forgives them, brings his father and brothers to Egypt to survive the famine.

Holy shit.

There it is.

So, Walter asked, are you your brother’s keeper or not?

Yes, I said.

Yes, he repeated.

And then he quoted Joseph’s words:

What you intended for evil, God used for good — for the saving of many lives.

And said…

That’s what Genesis means to me. I am my brother’s keeper.

I’ve thought about that moment for years.

Brueggemann taught me that the Bible is not primarily answering the questions we bring to it — the questions modern theology or systematic doctrine taught us to ask.

It’s answering ancient questions.

Human questions.

The questions of people trying to figure out how to live together without killing each other.

How to deal with family betrayal.

How to survive as a people.

How to make sense of suffering.

How to grieve.

How to hope.

And… Am I my brother’s keeper?

For many of us deconstructing now, Brueggemann opened a door for us years ago.

He didn’t destroy the Bible for us. He saved it.

He gave us permission to read it primarily as poetry and story.

He showed us that the Hebrew Scriptures are a living, multi-voiced conversation — not a static rulebook.

That the prophets are artists.

That lament belongs in worship.

That grief is holy.

That God doesn’t need to be flattened into a cosmic machine dispensing rewards and punishments, but can be found in the tension, the surprise, the ambiguity, the alternative imagination.

Walter was prophetic in the truest sense: not predicting the future — but exposing the system, naming the grief, and inviting us to imagine a better world.

I know many of you haven’t read him directly.

But you’ve probably read people who read him. His fingerprints are everywhere in this strange, beautiful corner of the world where questions matter more than answers.

If you’re curious, start with The Prophetic Imagination.

It’s not always an easy read, but it’s worth it.

Walter, thank you.

You helped me see that the imagination I brought to the Bible isn’t dangerous. It’s the point.

You showed us that only imperfect stories answer the biggest questions.

You taught us that we are our brother’s and sister’s keepers.

And that day at lunch, you were mine.

And now that you're gone, your words and legacy remain. Keeping us all brothers and sisters in a world where the biggest questions of humanity are answered only one way — through our inherited and lived stories.

P.S. If you’ve met or read Walter feel free to share your reflections in the comments. I know many of you have your own story of how his work made space for your journey.

Or, you can comment here for his family to read.

Virgin Monk Boy agrees: we are indeed our brother’s keeper. And not just the easy brothers—the annoying ones, the ones who post conspiracy memes, the ones who cut us off in traffic, the ones who broke our hearts. We should be praying for everyone we ever encounter—friend, stranger, enemy—because if we withhold compassion, we become the very system we lament.

Brueggemann got it: scripture isn’t a dusty rulebook, it’s a mirror held up to the raw ache of being human. Cain’s question echoes still. Virgin Monk Boy would add: “Yes, you’re your brother’s keeper. Now stop arguing and go make the soup.”

Thank you, Joe, for this space to share a grief and a challenge. My grief is that as a result of listening to a fellow student, I chose not to take any classes from Walter Brueggeman while I was a student getting my MDiv at Vanderbilt Divinity School. I have a deep yearning to learn more about him, his thought, and his impact.

One time several years ago, I got to hear him in a KY Disciples of Christ pastors’ meeting. I have retained my standing with the Disciples ever since my graduation in 1981.

I will also relate as a result of your lunch story that in many respects, I carry on Walter’s insight on Genesis. When I see my Muslim colleagues, I call them, brothers and sisters. Another colleague stated that they are not his brothers or sisters.

Last I checked, my humanity remains. So, I am brother to all humans. Being a human means that I am a keeper.

I keep myself. I keep my brothers, my sisters, and all other humans and this world to the best of my ability.

What is a keeper? A keeper is a lover, a lover of all.

Let’s do it