Josh McDowell and Verdicts That Demand Evidence

I grew up reading apologetics books that promised certainty. But deep down, I always knew something didn’t add up. This is the story of how I preached a sermon to convince myself and failed.

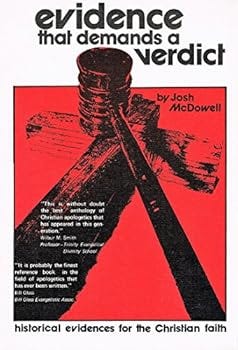

Evidence That Demands a Verdict

In 1991—my senior year of high school—I sat on my bed with a copy of Evidence That Demands a Verdict, trying to believe.

I would be heading to Bible college in a few months. Not because someone forced me. I wanted to go. I wanted to become a pastor. I wanted to make a life out of telling the truth about God.

But something already felt a little wobbly.

I wasn’t in a crisis. I hadn’t read anything radical. But I had questions. Quiet ones. Private ones. And I thought maybe this book could fix them.

Josh McDowell promised certainty. Logic. Proof.

I picked it up because I wanted certainty. I wanted something to stand on.

The Verdict I Wanted

I read Evidence That Demands a Verdict in my bedroom, alone.

Which, let’s be honest, is not what most high school seniors were doing in 1991. But I wasn’t most high school seniors. I was all in. Youth group kid. Teenage preacher. Bible Bowl champion.

And I just wanted to be convinced.

But the arguments didn’t land.

Even then, something in me could feel it—they were too confident, too neat. They felt like they were trying to win a debate, not tell the full truth.

Still, I wasn’t ready to stop believing.

So I did what a lot of us do when we’re scared and trying to stay faithful.

I convinced myself I’d been convinced.

I’d make a career of that as an adult.

I shelved the book. And the doubt. And I went to Bible college.

The Sermon I Preached to Myself

Fast-forward seven years. I was 25 and on staff at a large church. I’d been assigned a sermon titled Why We Can Trust the Bible.

I reached for the same book—McDowell’s greatest hits.

I built the case again. I stood in front of 3,500 people and gave it everything I had.

I explained the archaeology. The fulfilled prophecy. The manuscript evidence.

People loved it.

I got compliments, hugs, emails.

People twice my age lined up after the sermon and told me they felt reassured.

I said thank you.

But deep down, I knew: I hadn’t preached that sermon for them.

I had preached it for me.

I wanted to believe it.

I wanted that same certainty I had hoped for in my high school bedroom.

I wanted—what I gave them.

But as good of a young preacher as I was becoming,

I still couldn’t convince the one person in the room who needed convincing the most.

Me.

The Heretic Nobody Told Me About

Years later, I started hearing Bart Ehrman’s name.

Always with a warning. Always framed as dangerous.

He was the ex-evangelical who had “lost his faith” and was now out to destroy the Bible. The guy who poked holes in everything.

So I stayed away.

Until I didn’t.

When I finally read him, I was surprised—not just by the content, but by the tone.

He wasn’t mocking. He wasn’t bitter. He was careful. Respectful, even. And deeply committed to the work of telling the story behind the story.

Ehrman had started where I started:

Evangelical. Bible-believing. Passionate.

And to me, it seemed like he followed the evidence as honestly as he could—even when it took him somewhere unexpected. Unlike the approach I’d grown up with, where the conclusion was often predetermined, Ehrman let the questions stay open longer. He allowed the evidence to shift the ground beneath him. He didn’t lose his faith because he stopped caring. He lost it because he couldn’t pretend anymore.

Two Kinds of Thinkers

Looking back, I realize Josh McDowell and Bart Ehrman represent two very different kinds of thinkers—and two different kinds of trust.

McDowell—and later, writers like Lee Strobel—often say they began as skeptics. McDowell has said he set out to disprove Christianity and ended up convincing himself of its truth. And it’s not my thing to question someone else’s story. I don’t doubt McDowell’s or Strobel’s sincerity.

But the posture of their writing has always felt different to me.

It’s not really about open-ended exploration. It’s about building a case. (Strobel’s most famous book is literally called The Case for Christ.) The goal seems less about wrestling with complexity and more about reassuring the faithful.

They offer clear answers in a confusing world.

Maybe too clear.

At least for me.

They’re courtroom thinkers.

Faith as defense strategy.

There’s comfort in that. Especially when you’re young and afraid of getting it wrong.

Writers like Ehrman—and Marcus Borg, and John Shelby Spong—take another route.

They begin with the same Bible, the same questions, sometimes the same faith.

But they stay in the tension longer. They ask different questions.

And they’re willing to let go of tidy answers if those answers stop being honest.

It’s not that one side cares more or less about truth.

It’s that they define “truth” differently.

For one group, truth is something you protect, defend, and prove after the fact.

For the other, it’s something you uncover—even if it changes shape as you go.

Where It Brought Me

When it comes to my faith, I no longer have any need or desire to start with a verdict and look for evidence.

What I need is honesty baked in uncertainty.

Humility formed in curiosity and confusion.

The kind of trust that can breathe. Evolve. Change with the evidence.

Somewhere between McDowell and Ehrman,

Strobel and Borg,

Ravi Zacharias and Spong,

and a hundred other books I read hoping to find clarity—

I found my own voice.

And here’s what that voice is learning to say:

There are two ways to think.

There is evidence that demands a verdict.

And there are verdicts that demand evidence.

The irony is, the first apologetics book I ever read—Evidence That Demands a Verdict—felt a lot more like the second.

It started with the answer.

And then it built a case to back it up.

I’m not doing that anymore.

I’m not starting with the verdict.

I’m starting with the evidence—or the lack of it.

Just the quiet, stubborn work of sitting with my questions until they become more essential than any uncertain answer I can convince myself to try to believe.

This hit harder than any altar call I ever answered. I remember clutching Strobel’s Case for Christ like it was a spiritual seatbelt—hoping it would keep me from crashing into doubt. But all it did was tighten the tension between what I was told to believe and what I quietly suspected. Thank you for naming the quiet performance so many of us gave—not to deceive others, but to keep ourselves from falling apart. There's a strange kind of grace in admitting the sermon was for us, not them. That might be the start of real faith. Or at least, honest faith.

I was a non-believer until the age of 21. Raised in secular France. I read “Evidence that Demands a Verdict” and it left me with more doubts than I had before. I came to faith by reading the gospels.